It’s often said that you can tell how edible a mushroom is by the number of names it has. This concept certainly applies to the edible Flammulina velutipes, which goes by the common names Enokitake (and the shortened form Enoki), Velvet Foot, Winter Mushroom, and Golden Mushroom, as well as many other derivatives and regional names (if you’re outside the United States, you probably call it something else!). Another reason the species has so many names is because it looks very different in the wild than it does in the grocery store: in the wild, it grows as an orange umbrella-shaped mushroom with a black fuzzy stipe, but when cultivated it grows as a pale thin needle-shaped (or perhaps spaghetti-shaped) mushroom with a tiny pileus. I generally use the names F. velutipes, Velvet Foot, and Enoki, since each one emphasizes a different physical aspect of the mushroom.

Description

Natural Form

The Velvet Foot is an umbrella-shaped agaric that grows from dead hardwood in clusters that share a common base. Individually, these are small to medium-sized mushrooms, growing 1-7 cm across and 2-11 cm tall. The whole cluster, however, can get much larger – perhaps a foot or more – although I’ve never been lucky enough to find that many at one time.

When fresh, the pileus of F. velutipes is smooth but covered in a thin layer of slime, which makes it slippery to tacky (when dried out a bit). The cap is typically orangish with a lighter margin, although it can vary from reddish brown to bright orange to yellow-brown.

Underneath the cap, the Velvet Foot sports whitish to yellowish gills that are attached to the central stipe. The gills form close together and usually dip slightly before they connect to the stipe. Flammulina velutipes spores are white, so the mushroom will give you a white spore print.

The Velvet Foot’s namesake is its stipe, which is also its most distinctive – and beautiful – feature. When young, the stipe is yellowish or orangish and covered in tiny white hairs. As it matures, the stipe darkens to dark brown and develops a velvety texture (similar to the surface of a peach), progressing from the base upward. When fully mature, only the very tip of the stipe remains lighter and smooth, staying about the same color as the adjacent gills.

Cultivated Form

The cultivated form of F. velutipes is so dramatically different from the wild form that it has inspired many common names: Enokitake, Golden Needle, Futu, Lily Mushrooms, etc. The name Golden Needle is particularly apt: the cultivated mushrooms are mostly stipe, topped by a tiny pileus scarcely wider than the stipe. The colors are much paler than the normal form and range from white to light yellow. The largest cultivated enoki mushrooms measure roughly 30 cm long and 3 cm wide at the pileus, although dimensions are highly variable based on when the mushrooms were harvested.

You actually find the cultivated form in the wild, whenever the mushrooms begin growing underneath bark. The purpose of a mushroom is to release spores into the air, but a mushroom trapped underneath bark cannot accomplish this task because it has no access to the air currents. The cultivated form of F. velutipes is really just a clever solution to this problem.

First, the mushroom senses it is trapped under bark by measuring the amount of light and carbon dioxide. Bark blocks light and traps CO2 (like us, fungi breathe out CO2 as they grow, which leaves the wood and gets stuck below the bark), so the mushroom can tell if the environment is unfavorable when there is very little light and a very high CO2 concentration. Under these conditions, the fungus switches to growing in the cultivated form. Instead of devoting resources to expanding the cap, developing color, and producing spores, the mushrooms instead put all their energy into growing tall. This results in long thin pale mushrooms.

As the cultivated form mushrooms extend, they search for any cracks in the bark (places where light gets in and there is less carbon dioxide). Once they encounter a crack, they grow through the gap and escape into the external environment. Upon encountering open air, the mushrooms switch back to growing in the natural form: the pileus expands and develops color and the stipe becomes black and fuzzy. This process ensures the mushroom doesn’t waste energy on spore production until it is sure the spores can be successfully deposited into air currents.

The next time you find some Velvet Foot, peel back the nearby bark to see if you can find the cultivated forms as well! Unfortunately, I haven’t been lucky enough to document this phenomenon, but there are some great photos of it on the websites linked under “See Further.” Humans decided that the cultivated form is better for cooking, so we intentionally grow the mushrooms under conditions that mimic bark. This process is explained further under the “Cultivation” section, below.

Ecology

In the wild, F. velutipes can be found decomposing hardwood logs, usually with the bark still attached. Its fruiting season starts in fall and continues throughout the winter, which earned it the common name Winter Mushroom. However, you occasionally find the Velvet Foot at other times of year as well. It particularly likes warm spells in the winter and cold snaps during other seasons (whenever temperatures drop below 60°F for long enough to initiate fruiting). The mushrooms decompose various kinds of hardwood and will sometimes grow from roots or buried wood and may therefore appear to be growing terrestrially. The Velvet Foot seems to have a particular affinity for elms, so it is especially common in places recently impacted by a wave of Dutch Elm Disease.

Other Flammulina Species

Currently, there are 11 recognized species of Flammulina, but it seems likely there are at least two more hiding in Asia. All species in the genus have the distinctive black velvety stipe, making it easy to get to genus. Distinguishing the species, however, is best done with a microscope. Fortunately, you can get pretty close by looking at the pileus and checking the habitat.

In North America, there are five Flammulina species you have to consider. If the species is growing on poplar or aspen wood, then it’s F. populicola. If the species is found in high altitude areas of Mexico and is growing on a species of Senecio (usually Senecio cinerarioides), a woody member of the daisy family, then it’s F. mexicana. The remaining species can be tentatively separated based on pileus color: F. rossica (the most widely distributed species, which is found all over the northern hemisphere) has a pale to yellow pileus, F. filiformis has an ochraceous to yellow pileus, and F. velutipes has an orange-brown to yellow pileus.

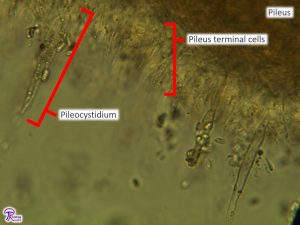

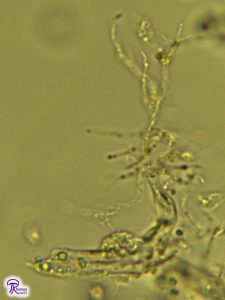

As you can see from the previous sentence, things get a bit confusing if your mushroom has a yellow pileus. In North America, F. filiformis seems to be restricted to Canada and mushroom farms and F. rossica sticks to Alaska and Canada. Unless you’re north of the continental United States or in a mushroom farm, you can call your yellow collection F. velutipes. If you find yourself in one of those places, however, you need to check spore size and microscopic features of the pileus. F. filifomris has distinctly unbranched vertical hyphae composing its surface. F. rossica has spores that grow as long as 11.9 µm (rarely up to 12.4 µm) and has some cells at the pileus surface that are inflated at the ends, while F. velutipes spores grow as long as 9.5 µm (rarely up to 11 µm) and has some cells on the pileus surface that are inflated toward the base of the cell but not toward the cell center or tip.

For more details on differentiating the species, see the table below. The spore sizes in the table are listed as length × width, with each dimension detailed as follows: (rare small size) lower limit–upper limit (rare large size). Q refers to the spore length divided by spore width, which gives you an idea of the shape of the spore: a Q value closer to 1 means the spores are more circular, a Q of 2 means the spore is twice as long as it is wide and is therefore likely an oval, and a very large Q would indicate a long needle-shaped spore. The pileipellis is the outer layer of the pileus and for Flammulina the important part of the pileipellis is the shape of the very outermost cells. Flammulina species typically have very large cells called pileocystidia interspersed with smaller cells that make up the pileipellis. The largest cells (pileocystidia) are considered separately from the pileipellis terminal elements, so ignore the pileocystidia when using the table. I know this gets confusing, but it’s slightly less confusing than reading the scientific literature (relevant papers are linked in the full citations section at the bottom, in case you need more detail).

| Species | Location | Habitat | Important Features | Spores | Q | Pileipellis Terminal Elements |

| F. velutipes | N. America, Europe | Broadleaves | Pileus yellow to orange-brown | 6–9.5 (11) × 3–5 µm | > 1.72, average about 2.2 | Branched or unbranched and inflated near the base |

| F. populicola | N. America, Europe | Populus (Poplar, aspen) | Similar to F. velutipes | 6–7.5 × 4–5.5 µm (shorter/wider than F. velutipes) | – | Inflated and club-shaped |

| F. mexicana | Mexico at high altitudes | Senecio (daisy family) | Pileus ochraceous buff to brown-orange with darker discolorations | 7.1–11.7 × 4.5–6.9 µm | 1.46–1.58 | Inflated-cylindrical to club-shaped |

| F. rossica | N. hemisphere | Broadleaves | Pileus whitish to yellowish ochraceous | (8.9) 9.2–11.9 (12.4) × (3.5) 3.6–4.9 (5) µm | (1.95) 2–2.82 (2.99) | Inflated at the middle or tip or club-shaped or branched |

| F. filiformis | East Asia, Canada, cultivated elsewhere | Broadleaves, cultivation | Pileus ochraceous to yellow | (4.5) 5–7 (8) × (2.5) 3–3.5 (4) µm | (1.42) 1.59–2.41 (2.85) | Vertical thin unbranched hyphae |

| F. yunnanensis | China | Broadleaves | Pileus yellow, stipe yellowish | (5) 5.5–6.5 (7) × 3–4 µm | 1.5–2 (2.33) | Inflated to club-shaped |

| F. elastica | Europe | Salix (willow), Populus (poplar, aspen) | Similar to F. velutipes (morphology might be insufficient to distinguish the two species) | (7.5) 8–11.5 (12) × (2.3) 3–4 (4.7) µm, larger than F. velutipes | 2.5–3, higher than F. velutipes | Similar to F. velutipes |

| F. fennae | Europe | Broadleaves | Pileus white to pale yellow (ochraceous when young), with darker splotches | (5.6) 5.9-7 (7.4) × (3.5) 3.7–4.3 (4.6) µm | (1.42) 1.49–1.74 (1.83) but when averaged < 1.8 | Unbranched and inflated near the end or middle |

| F. ononidis | Europe | Ononis spinosa (bean family) | Similar to other species, but generally smaller | (7.5) 8.5-13 (14) x (4) 4.5-6 µm | Average about 2.2 | Branched or straight, not inflated |

| F. finlandica | Finland | Salix (willow) with bark | Similar to F. elastica | (7) 8–12 (13) × (3) 3.5– 4.5 (5) µm (wider than F. elastica) | (1.75) 2.0–3.06 (3.44) | Branched (some unbranched), inflated near the end or middle |

| F. cephalariae | Spain | Cephalaria leucantha (honeysuckle family) | Pileus orange-red to brick red, sometimes yellow | (9.2) 12–16.8 (17) × (5) 5.6–7.6 (8) µm | 2 | Not inflated |

Similar Species

A velvety stipe, slimy pileus, and clustered growth should eliminate all other possible species. Of course, sometimes those features are just ambiguous enough to be confused with other species when they’re faded or have had their ornamentation washed away by rain. In those cases, there are too many possible options to consider them all here, so I’ll have to settle with a reminder to use the keys in your field guide and to check spore prints!

The most significant lookalike is Galerina marginata, because it is a deadly poisonous mushroom. Fortunately, there are several prominent features that can differentiate this species from the Velvet Foot. The most prominent feature is that G. marginata leaves a brown spore print. Galerina marginata also has a ring on its stipe (which often collects the brown spores on the upper part). Since Flammulina does not have a partial veil, it never forms a ring. Galerina marginata also has a brownish pileus that is typically semicircular and never slimy. Any one of these features is different enough to separate Galerina from Flammulina, so most of the time you won’t mistake these two species. The real danger is when you’re in a hurry and accidentally collect a G. marginata mushroom alongside your enoki. Remember to check every mushroom you collect and you should be able to avoid mistaking these species.

Another mushroom with a dark fuzzy stipe is Tapinella atrotomentosa. That species, however, is much thicker than Flammulina (the stipe can grow a few centimeters – or a couple inches – thick) and grows on conifer wood. Other species with fuzzy stipes include Panus lecomtei, Panus neostrigosus, Pleurotus dryophilus, and Pleurotus levis. The two Panus species are easily separated because they have decurrent gills and not much of a stipe. The Pleurotus species are easily distinguished because they are very large, white, and have decurrent gills.

Other clustered mushrooms that could be confused with enoki, at least when young, include Armillaria, Pholiota, Kuehneromyces, and Cyclocybe erebia. Most Armillaria species have a partial veil that leaves ring on their stipe, which helps separate them from the ringless Velvet Foot. One exception is Armillaria tabescens (now Desarmillaria caespitosa, which never forms a veil or ring. That species can be distinguished from F. velutipes because D. caespitosa grows on the ground around hardwoods in large dense clusters, is a light tan over all its surfaces, has a slightly fuzzy pileus, and has a smooth stipe. Pholiota, Kuehneromyces, and Cyclocybe erebia are a bit easier to distinguish because they all have brown spores and a partial veil.

Edibility and Uses

Flammulina velutipes is considered edible in field guides and F. filiformis is known to be edible thanks to its widespread cultivation. I find these species to have a great flavor and texture (in both the wild and cultivated forms), making them suitable for many kinds of dishes. Edibility has not been recorded for the other species of Flammulina. However, it is reasonable to assume they are edible because they are all so similar and have probably been misidentified as F. velutipes and consumed many times over the years with no reported ill effects. If you choose to eat these other Flammulina species, remember to try small amounts at first and report any adverse reactions to the North American Mycological Association to increase our knowledge of mushroom edibility.

Actually, 36 cases of food poisoning – including four deaths – were associated with F. filiformis (labeled as F. velutipes) in the United States in 2020. However, these cases were the result of contamination with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. All the cases were from contaminated cultivated mushrooms purchased at stores across 17 states, underscoring the importance of sterile cultivation practices and proper food preparation and storage.

The most widespread use of Flammulina is as an edible cultivated mushroom, but the fungus has other uses as well. Scientists have been interested in its ability to decompose lignin as well as the developmental implications of the cultivated growth form. In particular, F. velutipes provides good evidence that mushrooms use hormones to coordinate fruitbody growth. When you cut the cap off of a growing mushroom, the stipe stops growing (a result not seen in all mushroom species). This implies that the F. velutipes pileus produces some substance – a hormone – that is sent to the stipe to tell it to keep growing. My own research uses F. velutipes and seeks to understand what genes are responsible for controlling the various stages in mushroom development as well as the switch from the natural to cultivated growth forms.

Enoki also has the distinction of having been grown in space. In 1993, the mushrooms were sent up aboard the space shuttle Columbia. Some were spun around to simulate gravity and others were left to float around in space. The spinning ones all oriented their caps in the same direction, while the floating ones grew in random directions. This was an expected result and demonstrated that gravity is indeed important for determining which direction mushrooms will grow.

Cultivation

Enoki grown for commercial sale is generally grown in jars on a mixture of sawdust and rye. Flammulina species are hardwood decomposers, so the sawdust provides their food. A little bit of rye grain is added as a nitrogen source, which promotes mushroom formation. The sawdust-rye jar is sterilized in an autoclave (basically a large pressure cooker) for a couple hours before the fungus spawn (typically a grain such as rye that has been fully colonized by fungal mycelium) is added. The jar is then shaken to evenly distribute the spawn, which then slowly grows into the rest of the jar over the course of a few weeks.

Once the jar is fully colonized, it is moved into the fruiting chamber. This area is kept dark and at 60°F. The cool temperature stimulates the fungus to start producing mushrooms while the darkness prevents the cap from expanding. Additionally, a paper or plastic collar is placed around the top of the jar to increase the concentration of CO2 near the mushrooms, stimulating them to grow tall. The end result is kind of like the mushroom version of a Chia Pet. Once the mushrooms reach the top of the collar, they can be easily harvested by grasping the bunch and giving a gentle tug – the whole clump comes out at once with a satisfying soft pop.

Taxonomy

Flammulina velutipes belongs to the main group of gilled mushrooms, the Agaricales. Beyond the Agaricales, F. velutipes belongs to the family Physalacriaceae, a rather small family whose most notable members are Flammulina and Armillaria (the Honey Mushrooms)

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Subkingdom | Dikarya |

| Division | Basidiomycota |

| Subdivision | Agaricomycotina |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Subclass | Agaricomycetidae |

| Order | Agaricales |

| Family | Physalacriaceae |

| Genus | Flammulina |

| Species | Flammulina cephalariae Perez-Butron & Fernández-Vicente Flammulina elastica (Sacc.) Redhead & R.H. Petersen Flammulina fennae Bas Flammulina filiformis (Z.W. Ge, X.B. Liu & Zhu L. Yang) P.M. Wang, Y.C. Dai, E. Horak & Zhu L. Yang Flammulina finlandica P.M. Wang, Y.C. Dai, E. Horak & Zhu L. Yang Flammulina mexicana Redhead, Estrada & R.H. Petersen Flammulina ononidis Arnolds Flammulina populicola Redhead & R.H. Petersen Flammulina rossica Redhead & R.H. Petersen Flammulina velutipes (Curtis) Singer Flammulina yunnanensis Z.W. Ge & Zhu L. Yang |